What Would Columbus Do?

Is shipping really more complicated today? Given current technological and regulatory developments, one can easily feel overwhelmed. So many decisions to be made for bunker fuels alone. Looking ahead, there are so many more innovative developments on the horizon that could affect how ships trade and sail in the future.

One would think that making decisions in the maritime industry today is hard (which it is). Some might say that our generation has it harder than previous generations when it comes to decision-making in shipping because life was simpler then.

But was it really?

A Backward Look

While visiting the Casa de Colon (House of Columbus) in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, recently, which in our opinion is one of the important maritime museums in the world, we had the serendipitous opportunity to be exposed to a unique historical perspective that has made us question some existing preconceptions.

The Casa de Colon is the house where Christopher Columbus stayed on the eve of his epochal voyage to America. His small caravel, La Nina, had been damaged from bad weather since leaving Cadiz, and Columbus needed a place to take on more provisions for his unknowingly long voyage.

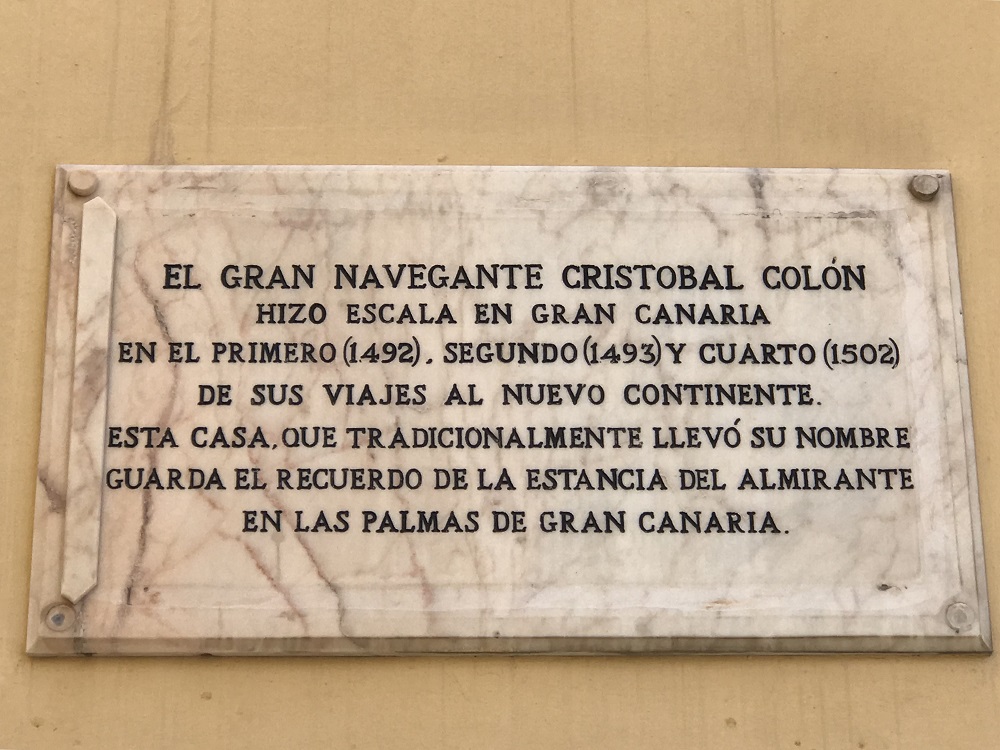

Sign at the Casa de Colon, Las Palmas: "The great navigator Christopher Columbus visited Gran Canaria on his first (1492), second (1493) and fourth (1502) trips to the New World. This house, which traditionally bears his name, keeps the record of the admiral's stay in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria." (Image courtesy Basil Karatzas)

Courtyard of the Casa de Colon (Basil Karatzas)

The edifice itself is a charming two-story stone building situated in the old town of Las Palmas (La Vegueta) with an interior central court around which the house is situated, complete with framing balconies hanging all around the court, a water well, a stone tub, tall-ceilinged rooms, a magnificently vaulted basement, and amazing architecture and attention to detail all around. That such a house is today a maritime museum is so historically prescient and appealing, so conducive to visualizing a 42-year-old aspiring navigator preparing for a trip that no one in human history had knowingly undertaken before, busily making last arrangements for his three ships for a voyage in a vast unexplored ocean to a fantastic destination. This was his last landing before taking on the ocean, discovering a New World and making history.

Surely many decisions had to be made for the whole voyage, but we will focus here on the type of vessels used for the voyage and their sailing arrangements. In 1492, the year of his first voyage, wind was the predominant mover for powering ships, and until then even extensive sailing voyages were usually along coastal lines and not too far into the open sea. It was then just about the time for the great age of exploration, the age when the great navigators were setting out to make the world a smaller place.

But no one before had explicitly taken on to cross a vast open ocean with a sailing boat, just coastal trading before then. What were the predominant directions and strength of the winds in the ocean? Some hypotheses, but nobody really knew. And what would be the best way to harness wind power to propel the ships when no one really knew about the ocean’s prevailing winds?

Columbus was originally from Genoa and first mastered sailing and navigating in the Mediterranean Sea. He was extremely knowledgeable about several types of lateen ships, ships with one or more masts and triangular sails hoisted from each mast, sails whose angle to the wind could be changed by easily adjusting their orientation in reference to the axis of the ship and direction of the wind – something that could easily be done with little manpower onboard. Lateen ships resemble, in their sailing arrangement, today’s sloops and recreational sailing boats, and they are indeed easily maneuverable and can sail against the wind. Lateen ships dominated Mediterranean trading history, and their existence goes back to the age of the Phoenicians (circa 1000–300 BC).

Encountering the Unknown

However, Columbus was preparing for a voyage in an unknown vast open ocean. Lateen sailing arrangements (velas latinas) had not been known for enough output to propel relatively big and heavy ships over large distances simply because they cannot sufficiently catch enough wind.

A relatively newer type of sailing ship was evolving at that time, the carrack, with a bulkier hull (casco redondo) but still with lateen-arrangement sails. This type of vessel was the precursor to the square-riggers where large, almost square sails hoisted from the masts at a right angle to the axis of the ship. Because of their size and positioning, square-rigged ships can be big and sail over long distances. After all, the clipper ships were square-rigged, and Britain’s glorious naval superiority was eventually based on elaborately square-rigged ships.

At the time of Columbus’ first voyage, however, square-rigged ships were a rather new innovation, small in size (Columbus’ largest ship, the Santa Maria, was approximately 120 tons) and of little help for a vast voyage. On the other hand, square-rigged ships were the only known way to propel ships over long distances. The typical square-rigged ships at the time of Columbus were carracks (Nao in Spanish) of approximately 100 tons, and the typical lateen-rigged ship of the time were caravels of approximately 50 tons. And just to emphasize the order of magnitude, a modern-day supertanker is approximately 320,000 deadweight tons.

Thus Columbus, when preparing for his voyage, had choices to make, like any modern-day captain, like any modern-day shipowner. Should he proceed with caravel vessels or carracks? Lateen or square-rigged? Again, he knew precious little about his voyage in terms of distances and winds – just rudimentary calculations that proved miserably wrong in retrospect. His choice of powering his ships was of personal importance since he had bet his professional reputation to get started and hopefully get the extravagant title he was promised (“Admiral of the Oceans”).

It was of tremendous economic importance as his patrons, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, were promised certain rewards and pots of gold for sponsoring this expedition, and Columbus himself stood to get a 10 percent cut of any profits. It was of existential importance as well since the survival of his sailors and his own life could depend on this decision alone. And, for whatever its worth, it was of historical importance too since the survival and success of the mission would change the course of history – as indeed it did.

Based on information at the Casa de Colon, Columbus seemed to agonize over his choice of ships for his first voyage. Of course, he had to do so with a rather limited budget. But there was a lot at stake in choosing correctly between limited power with maneuverability and novelty gross sailing power with limited maneuverability.

In retrospect, Columbus seems to have hedged his bets by choosing two types of ships and both sailing arrangements for his first voyage: He opted for two caravel-style ships with svelte hulls (the Pinta and his beloved Nina) and a carrack with a bulkier hull as his flagship, the Santa Maria. He had both the caravel Nina and the carrack Santa Maria replace their lateen sails with square sails (as caravela redonda) that ensured as much “power” as possible to make the voyage.

Making Tough Decisions

At the end of the day, most of human history will remember Columbus well – for his choice of sailing ships and sail arrangements – among many decisions for his first voyage. And as far as tough decisions in shipping are concerned, they seem to be an everyday fact of life, at least since the age of Cristobal Colon five centuries ago. Scrubbers and new technologies in shipping and what-not, this industry has faced it all – even when the stakes have been much higher!

Basil M. Karatzas is the CEO of Karatzas Marine Advisors & Co., a shipping finance advisory and ship-brokerage firm based in the New York City. Basil has more than fifteen years of shipping market expertise, holds an MBA in International Business and Finance from Rice University in Houston, Texas, and has graduated from the Owner / President Program at Harvard Business School.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.